Oregon Coast Agates: The Storm Season

Winter on the Central Oregon Coast is when the true rockhounds show up. The crowds thin, the fog rolls in, and the ocean starts to breathe differently. The same storms that send tourists running are what bring the agate hunters out in their best rain gear. We know that when the waves rage, the shoreline resets. And when it resets, it reveals.

The day after a big storm is the moment every beachcomber waits for. The sea has churned through its layers, pulled back its blankets of sand, and rolled its treasures to the surface. It’s a game of timing, luck, and persistence. The early-bird rule applies, the first tracks across the high-tide line often come with the best finds. The wilder the weather, the better the churn.

“Follow the Storm—Find the Stone”

The Storm Season Rhythm

The Central Coast in winter is wild in every sense. Fog flows like river water through massive sitka spruce trees. Salty air and sea spray hang thick enough to taste. Waves hammer the headlands and explode into walls of mist and white foam. The whole place hums with energy.

After a strong surge, beaches that looked smooth and sandy for weeks can suddenly turn coarse overnight. Gravel shows through, and to a rockhound, that’s the signal. A beach that felt ordinary can suddenly feel rewritten. Cliff erosion exposed, cobble pushed into ridges, kelp shredded and tangled, a few crab pots stranded high, and somewhere in that chaos, glowing bits of chalcedony waiting to be noticed.

You can almost hear the change before you see it. Locals call it the sound of “magic rocks” — the rattling, tumbling noise as waves pull surf-polished basalt, dacite, and microcline back down the beach slope. It’s hypnotic, a reminder that coastal geology never rests.

Reading the Storm

When you hit a beach after a storm, your eyes start scanning instantly. It’s instinctual. The first thing you’re looking for is texture — gravel and cobble, not sand. The less sand, the better. If you see fresh boulders or cliff debris where there wasn’t any before, it means the surf reached higher and harder than usual. That’s when you get the “oh wow” moment and start moving.

Reading a beach is about memory as much as observation. You remember how it looked last week, last month, last winter. You notice what’s new, where drift lines shifted, where water cut deeper channels, where bedrock or gravel bars suddenly sit exposed. Storms don’t just rearrange material; they redraw the map.

Sneaker waves are real, and they don’t care if you’re mid-find. Staying alert isn’t about fear…it’s about respect. Use your peripheral vision. Learn to look down and up in rhythm. One eye on the horizon, one on the stones. It’s a quiet dance between you and the sea. The best window is usually the first outgoing low tide after a storm passes. That’s when the ocean exhales.

What to Look For

Water is your best friend this time of year. Everything looks better wet. Stones that seem dull in the summer sun come alive under a gray sky. When soaked, agates and other chalcedony stand out against black and gray cobble. They might resemble ice cubes, amber, or honeyed glass—subtle clues of microcrystalline quartz catching winter light.

Train your eyes to notice anything that breaks the pattern. Most gravel is opaque, meaning light does not pass through it. Jaspers are typically the opaque variety, while agates are translucent expressions of the same mineral family: chalcedony. That said, agate as a term has nuance. Without distinct features, it’s more accurate to call many finds translucent chalcedony.

A signature trait of an agate is diaphaneity (its ability to transmit light), often paired with banding. That banding may be concentric, fortification-style, waterline, or a blend. Some agates lack visible banding altogether and still qualify, while others sit in between categories, confusing even seasoned collectors. That spectrum is part of the draw.

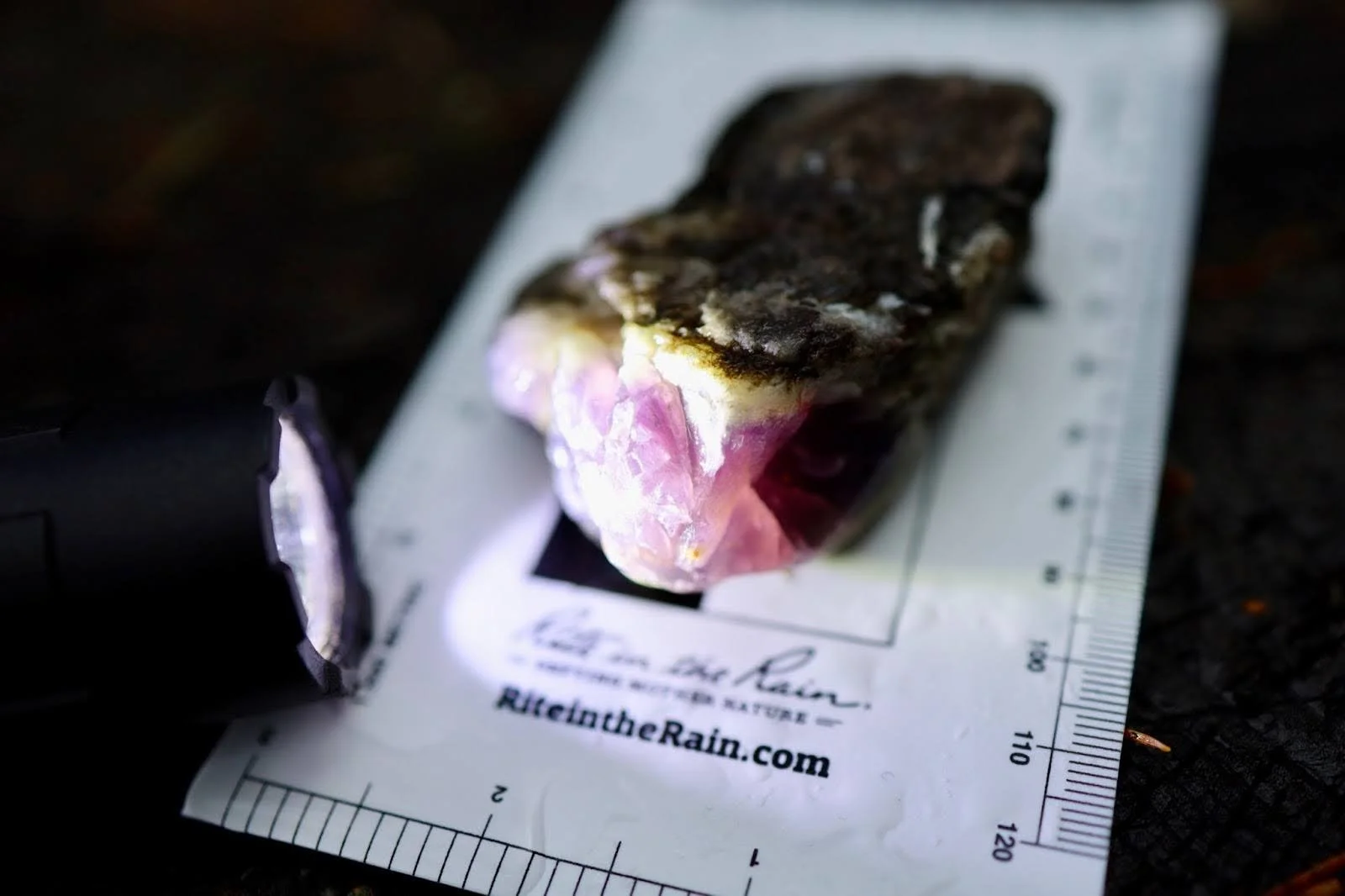

A simple field test helps if you’ve found chalcedony: hold the stone up to a flashlight, or the sun if it’s out. If light passes through, you likely have an agate. If it doesn’t, it’s probably jasper. If it’s somewhere in between, you may have a jasp-agate or something else entirely.

Some stones flash fiery orange or blood-red carnelian. Others glow milky white or smoky gray. And once in a while, the coast offers something rarer—blue-black material or even a purple “Agathyst.”

Half the time, you don’t know what you’ve found until you pick it up. I’ve mistaken broken jellyfish for agates more than once. That pause between curiosity and confirmation is part of the magic; if something catches your eye, even briefly, give it a second look.

The Hunt

Everyone has their own method. Some grid a beach end to end. Others zigzag between tide lines. Some walk fast out and slow back. I start where the stones are thickest and work outward if time allows.

If others are out, that’s a good sign. But the real trick, one learned through years of watching patterns, is skipping easy-access zones. Don’t linger near the stairs. Push to the far end first. Most people never make it that far.

When you do find something good, stop. Turn it in your hand. Look for fractures, host rock, color, and character. Every stone has a fingerprint. Some belong in your bag. Others stay right where they are. Knowing the difference is part of the craft.

Erosion and the Earth Below

The Central Coast’s agates come from deep time, with the help of volcanic lava flows millions of years ago. Basalt and dacite dominate the parent geology in many areas here. Over time, silica-rich groundwater moved through fractures and voids, filling cavities and slowly precipitating chalcedony.

As cliffs erode, those nodules break free. Waves do what rock tumblers do: grind, abrade, polish, and reveal internal structure. The ocean is the oldest lapidary machine on Earth, and winter storms continue that work. Landslides, exposed bedrock, and freshly broken host rock all signal opportunity. This isn’t destruction—it’s renewal.

King Tides and Coastal Power

Each winter brings three or four King Tides. The highest tides of the year, when sun, moon, and Earth align. They’re spectacular and dangerous in equal measure.

Depoe Bay is famous for storm watching. Whitewater erupts along the seawall in thunderous bursts. It’s no time for collecting. Rockhounding is best saved for after, when water retreats and the coast reveals what’s been stirred loose.

King Tides don’t just move sand, they redistribute entire mineral assemblages.

Notable Winter Beaches

From Cascade Head to the Oregon Dunes, opportunity is everywhere. Roads End and hidden coves north of it shine after erosion events. Fogarty Creek remains a hotspot for quintessential Oregon Coast agates and excellent marine fossils.

Otter Rock through to Beverly/Moolack Beaches are reliable for smaller agates and fossils too. This is one area where you’re able to see the incredible bedrock of the seafloor when it gets exposed.

Nye and South Beach occasionally produce the famous Newport Blue/Black material near the jetties. Farther south, beaches between Yachats and Neptune yield prized carnelians and sagenitic agates with sprays of acicular needle-like inclusions.

“Where there’s one, there’s more”

INDRA ON THE STORM SEASON: A Rockhounding Kid’s-Eye Q&A

Q1. What does the sky look like before your favorite kind of storm?

Dark and misty. Foggy gray. I love when it gets that way.

Q2. You’re named after the god of rain. Does that make storms feel extra special to you?

Yes. Sometimes it even feels like my emotions help make the storms. If I’m laughing really hard, maybe it hails. If I’m happy, maybe there’s a rainbow. When there’s a huge atmospheric river, it feels like freedom.

Q3. What do you like most about the rain?

When the rain blows on my face, it feels refreshing. It makes me feel alive.

Q4. Do you think the beach looks different after a storm?

Yes. The sand gets all wavy because the tides make these little ripples, and it looks different every time.

Q5. When storms come, what do you hope the ocean leaves behind?

Beautiful treasures. Beautiful things to see. I hope it leaves sea treasures on the beach for you and for me.

Q6. When you’re walking the beach after a storm, what sounds do you hear?

Sometimes the clouds are rumbling and other times the seagulls squawking. Also the waves dragging the rocks back down the beach. I love that sound.

Q7. When you walk a winter beach hunting for agates, what do your eyes look for?

I’m just looking around, seeing what I can find. I always find something new. I surprise myself a lot.

Q8. What’s your favorite color of agate, and why?

Blue agates—because they glow under UV light. And purple Agathyst—we’ve only ever found one, so it’s rare and beautiful.

Q9. What’s the coolest thing you’ve ever found with your dad?

An arrowhead. We were crossing this river, drifting downstream. As soon as we got out, there it was, sticking out from under a rock. A real agate arrowhead from a Native American tribe. It was amazing!

Q10. How do you know when a stone is a keeper?

A “leaver” is a stone that is tiny, brittle, fractured, or just very common. A “keeper” is a stone that is bigger, solid, stable, or really rare…like my raindrop geode! Plus you can’t keep everything. You have to be a little picky with what comes home.

Q13. If the ocean could talk, what would it say to you?

Nothing. It would just wave.

Q14. What’s the best smell after a long, rainy night on the coast?

Salty, misty sea air mixed with bonfire smoke.

Q15. If someone was scared of storms, what would you tell them to help them see the magic?

It’s okay to be scared. The ocean, the trees, and the whole coast would be different without Storms. You have to embrace where you live.

Q16. If you could tell other kids one secret about the coast, what would it be?

If you want cool stones, check out Fogarty Creek. The far side. That’s where we find the glowy green stones!

By the end of the storm season, most of us are soaked through, shoes full of gravel, and hearts full of gratitude. There’s a rhythm to this kind of work, the cycle of chaos and calm. The storms take, the storms give, and we meet them somewhere in the middle. When the clouds lift and the rivers settle, attention shifts inland to the headwaters and the Coast Range. That’s where spring’s adventure begins. But winter is where the real magic happens.

It’s the time of year this entire brand, this whole story, began for me—standing on a secluded foggy beach in 2021, seeing light in the stones that no one else saw yet. That moment still repeats itself every winter, every storm, every hunt.

Local’s Cheat Sheet: The Storm Season Quick Guide

Timing: The day after the storm is best. Aim for outgoing low tide after high surf.

What to Look For: Gravel beds, exposed cobble, any translucent “ice cube” shapes, or anything that breaks the pattern.

Safety: Sneaker waves are real. Never turn your back on the ocean.

Tools: Your best rain gear, mesh bag, waterproof flashlight, rain gear, gloves/hand warmers, UV light for night checks.

Hotspots: Road’s End, Fogerty Creek, South Beach, Yachats, Neptune.

Ethics: Leave it better than you found it, know your collection limitations, and respect private property.

Motto: “Where there’s one, there’s more.”

Eric Davis is a coastal guide and lapidary instructor based on Oregon’s North Coast. Through his platform Oregon Coast Agates (@oregoncoastagates on Instagram), he shares stories, fieldcraft, and photography that celebrate the untamed beauty of the Pacific’s stone and surf.