Willamette Pass: Grit, Snow, and Magic on the Mountain

On a cold Christmas morning not so long ago, Willamette Pass Ski Area had every reason to give up.

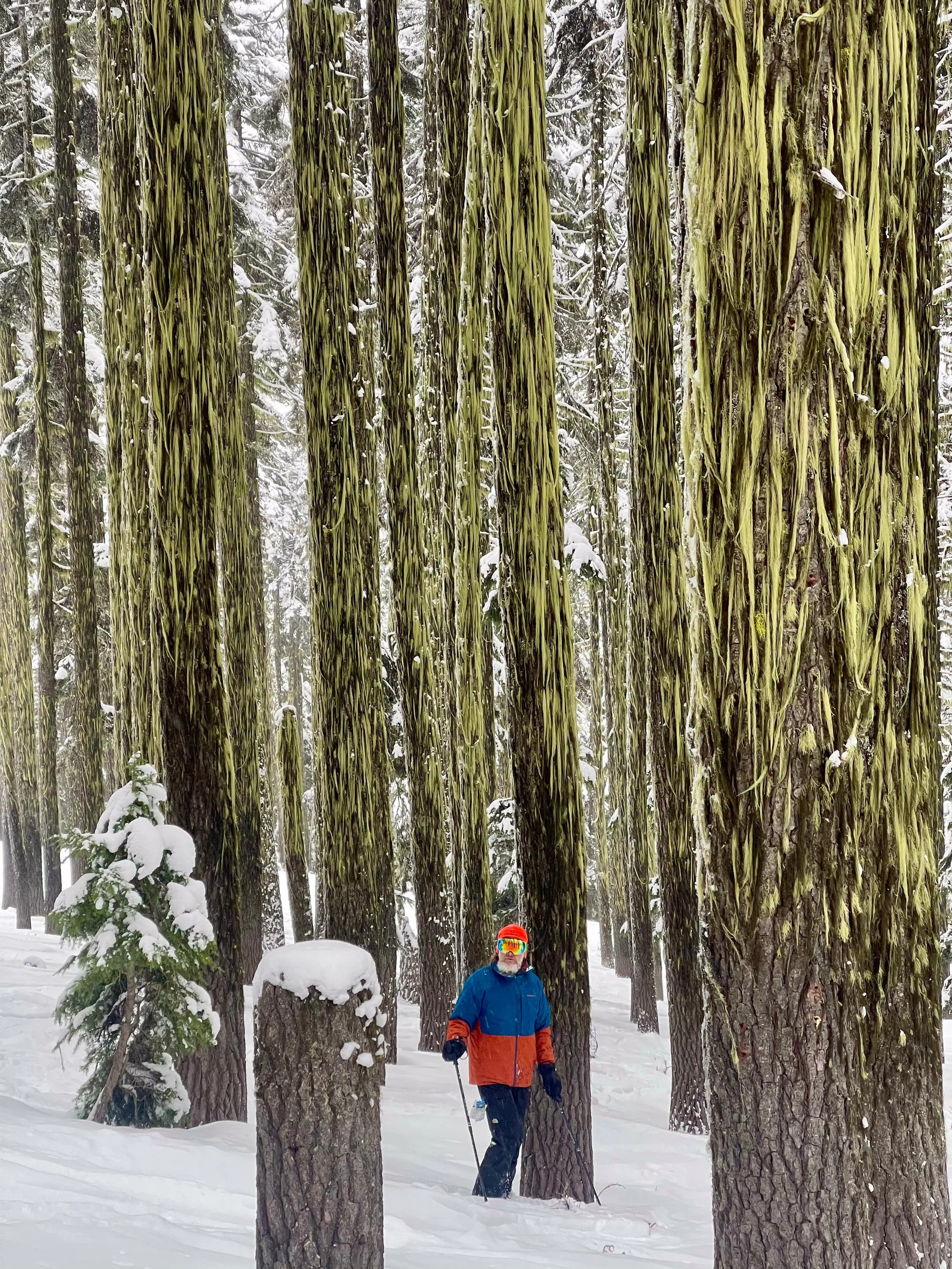

The winter had started badly—too warm, too wet, and far too dry in all the wrong ways. For a low-elevation, south-facing ski hill in Oregon’s Cascades, that combination is a nightmare. Yet as families wound their way up Highway 58 from Oakridge, La Pine, Crescent, and beyond, the lights were on, the lifts were spinning, and a thin but carefully farmed ribbon of white snaked down the hill.

It wasn’t luck. It was grit, snowmaking, and a crew of die-hard locals—many of them from Oakridge—who were determined to get at least a magic carpet and Sleepy Hollow open for the holidays. And despite the lack of precipitation over New Year’s day, kids who had been glued to screens since the week before Christmas were learning to slide on snow instead. Kids and adults alike also expereinced the first re-opening of weekend night skiing at Willamette Pass in a very long time.

That stubborn insistence on opening the mountain, even in the worst conditions on record for Christmas Day, captures the story of Willamette Pass: 84 years of improvisation in the face of shifting economics, changing climate, and a legal and insurance landscape that would send many operators running for the door.

And yet, today, Willamette Pass is not just hanging on. It’s growing, modernizing, and doubling down on its identity as an accessible, community-scale mountain that still feels like a classic Oregon experience.

From Rope tow to Six-Pack

The history of Willamette Pass starts with Oregon’s classic brand of mountain stubbornness. In 1941, Roy and Edna Temple logged a slice of Eagle Peak and installed a rope tow, creating one of the earliest ski areas in the United States to operate under a U.S. Forest Service special-use permit. Before the permit, people were already skiing here on informal slopes patrolled by volunteers from groups like the Obsidians and the Eugene Ski Laufers, who set up portable rope tows and took Red Cross first-aid classes just to keep their friends safe.

For decades, the hill remained rustic—a few tows, a lodge, and a whole lot of do-it-yourself spirit. In 1982, the Wiper family of Eugene, known locally for their funeral home and cemetery business, took over operations and installed the first chairlift, pulling the area into the modern era while keeping it firmly grounded in local ownership.

Willamette Pass quietly built a reputation that belied its modest size. Today, the resort offers 555 acres of skiable terrain and 1,563 feet of vertical, with 29 named runs served by a high-speed six-pack and four triple chairs. The mountain is best known for the line, RTS—“Really Tough Skiing”—a notorious pitch that hits 52 degrees at its steepest point, that hosted the 1993 U.S. Speed Skiing Championships, with record breaking top speeds up to 111 miles per hour.

But for every expert eyeing RTS, there’s a family lapping Duck Soup or By George, the broad groomed runs that form a kind of communal backyard for Eugene, Oakridge, and surrounding communities. On weekends, the day lodge fills with junior race teams, brown-bag lunches, and the layered accents of long-time locals and new Oregonians just discovering the hill.

That mix—serious terrain, approachable scale, and a scrappy, local culture—is what turned a simple rope tow into the backbone of several small-town winter economies.

A Mountain that Raised a Generation

Ask General Manager Mindy Ingebretson-Wolowicz how Willamette Pass shapes a community, and she starts with the kids.

She first talked her way onto Junior Ski Patrol in the early 2000s, at a time when “everyone was snowboarding,” and she was still figuring out her turns. What began as a teenage patrol gig turned into a lifelong relationship with the mountain, one that now includes taking her nephew up with a radio so he can roam the hill, make new friends, and learn what it means to be trusted in a big, wild place.

Programs like Youth Ski League and Junior Ski Patrol have given generations of kids from Oakridge, La Pine, Crescent, Gilchrist, and the lower Willamette Valley a place to grow up with real responsibility—learning avalanche awareness and first aid, running toboggans, or simply navigating the social geography of a lift line. That early exposure can change the trajectory of a life.

In a small, working-class town like Oakridge, where much of the winter economy now hinges on outdoor recreation, the significance is hard to overstate. Willamette Pass is the closest ski area, just about 20 miles up Highway 58. Many of the resort’s staff live in Oakridge, and on stormy mornings you can sense the steady flow of the local workforce making their way up the mountain long before first light—an early-day ritual that reflects just how deeply the community is tied to the ski area.

The mountain gives those communities more than seasonal jobs. It offers a shared story. Ask around Oakridge or Crescent and you’ll hear the same refrain: “I learned to ski at the Pass.” It’s where grandparents introduce grandkids to snow, and where teenagers who might otherwise drift away from small-town life get a taste of leadership and independence instead.

The Climate Reality: Warm Winters, Hard Choices

If this were just a nostalgia story, it would be easy. But the climate data out of Oregon’s Cascades doesn’t let any ski area pretend that the past will look like the future.

Research from Oregon State University shows that the Oregon Cascades have experienced some of the largest snowpack declines in the western United States since the 1920s, and that low-elevation snow is particularly vulnerable as temperatures rise. In a widely cited study, OSU geographer Anne Nolin and colleagues modeled how often “warm winters”—years in which mid-winter precipitation falls mostly as rain instead of snow—might occur at northwest resorts.

For Willamette Pass, they found that warm winters historically occurred about 3% of the time. In the modeled future scenario, that jumps to 67%—roughly 22 times as often. For a south-facing resort with a base elevation just over 5,000 feet, those numbers aren’t abstract. They show up as patchy snow on opening day, mid-season rain events, and the kind of roller-coaster temperatures that make grooming and operations a daily puzzle.

Across the Pacific Northwest, similar studies and industry analyses point to steep declines in reliable snow at lower-elevation hills, with potential season-length reductions of 80% or more in some scenarios. The impacts go far beyond skiing—earlier snowmelt shifts streamflow timing for rivers like the McKenzie and Deschutes, and the Middle and North Fork Willamette; complicating everything from salmon recovery to hydropower operations.

For communities like Oakridge, La Pine, and Crescent, the question becomes stark: how do you build a resilient local economy when the snow you’ve depended on might not always show up?

Reinventing the Operating Model

The current chapter of Willamette Pass is about answering that question in real time. In late 2022, Mountain Capital Partners (MCP) entered a joint venture to operate the resort, bringing the Pass into a portfolio of small and mid-sized ski areas across the West and Chile. MCP is known for heavy investment in snowmaking, infrastructure, and creative ticketing products, and Willamette Pass has already seen that philosophy put to work.

Under MCP’s ownership, the resort has:

Expanded and modernized its snowmaking system, adding more efficient guns and refining “snow farming” techniques to stretch thin early-season coverage as far as possible.

Improved sustainable infrastructure, right down to replacing lodge toilets with low-flow fixtures and mowing key trails so they can open on less snow.

Reactivated older lifts like the Midway chair and brought in new snowcats to improve grooming reliability.

In other words, the mountain is doing everything it can to turn fickle Cascades weather into a workable operating season. At the same time, MCP’s Power Pass model has made Willamette Pass one of the most affordable and inclusive ski experiences in the region. Kids 12 and under receive a completely free Power Kids season pass—no parent purchase required, no blackout dates, and access to all U.S. Power Pass resorts. Super-senior passes extend similar generosity to skiers 75 and older, and dynamic ticket products keep entry-level day tickets surprisingly accessible compared with bigger corporate hills.

For families in Oakridge or Crescent, where disposable income is tight, those details matter. They’re the difference between skiing as a luxury and skiing as a shared community activity—and it shows up with more locals returning to the mountain.

The Master Plan: Doubling Down on a Four-Season Future

Of course, no amount of creative pricing matters if the hill can’t operate. That’s where the Willamette Pass Master Development Plan comes in.

As part of its U.S. Forest Service special-use permit, the resort has developed a long-term Master Development Plan that sketches out a more resilient, four-season future. While the full document can be hard to access online, public reporting and resort communications outline a bold vision: doubling the skiable acreage, adding six or seven new lifts, expanding beginner terrain, building on-site employee housing, and improving base-area facilities and parking.

One of the most exciting elements is the phased build-out of West Peak, terrain that has appeared as a tease on trail maps for decades. The expansion would add more intermediate and advanced runs, helping spread skiers out and giving Willamette Pass the capacity to relieve crowding at larger destinations like Mt. Bachelor and Mt. Hood.

Equally important is the emphasis on beginner and family terrain. A new, expanded learning center with additional surface lifts and green runs would help grow the next generation of skiers and riders—critical for a resort that wants to remain inclusive, not exclusive.

But the plan isn’t just about winter.

According to Jason Nehmer, local disc golf event promoter for the 2024 Mountain Town Throwdown, “the thrill of throwing down the mountain utilizing preexisting ski trails is unmatched to anything I’ve experienced. This opportunity has unlocked this region’s highest potential for our sport while also showcasing a sustainable summer operation activity for the mountain. The future looks bright for disc golf at Willamette Pass!” Jason’s event also hosted a paint-out workshop with local artist Barbara Council, drawing participants to the top of the mountain to put Diamond Peak to canvas. Other events, such as the 2024 Pond Skim DJ Party which drew a flock of both spectators and competitors to take advantage of spring conditions, while watching participants slide across a large “puddle” of water from one icy end to the other, at the end of the primary ski run down the face of the mountain to the lodge. (Truly, entertainment at its best.)

The Master Development Plan and related concepts imagine summer and shoulder-season opportunities that take advantage of the mountain’s lift infrastructure and scenic position above Odell Lake: hiking, sightseeing, disc golf, and—eventually—lift-served mountain biking, provided Oregon’s recreation liability and insurance landscape can be stabilized.

In a state where mountain bike parks like Mt. Hood Skibowl have already closed their bike operations due in large part to soaring insurance costs and uncertain liability protections, the stakes are high. Without reform, Oregon could become the only western state where year-round lift-served recreation on public lands is economically impossible.

That’s why Mindy and other resort leaders are increasingly candid about the need for readers to contact their legislators and support balanced recreation liability reform that protects both participants and providers. Trade associations like the Pacific Northwest Ski Areas Association warn that without a fix, small and mid-sized ski areas face an “existential threat” from skyrocketing insurance costs and dwindling coverage options.

The message is simple: if Oregonians want places like Willamette Pass to survive, they need a policy environment that treats outdoor recreation as a shared value worth protecting.

A Regional Economic Engine, Not Just a Ski Hill

It’s easy to view Willamette Pass as simply a place for recreation, but for Oakridge, La Pine, Crescent, and the broader region, it operates far more like essential infrastructure. On a typical winter weekend, hundreds of cars and buses travel Highway 58 to reach the resort. They pass through Oakridge, where coffee stands, gas stations, and small restaurants make a significant share of their winter revenue from ski traffic. Many skiers stay overnight at Odell Lake, Crescent Lake, or in short-term rentals that stretch from the upper Willamette watershed to central Oregon.

Zooming out, Oregon’s outdoor recreation economy generates an estimated $16 billion in economic activity, $10 billion in payroll and benefits, and supports roughly 245,000 jobs statewide. Ski areas and bike parks are a visible, high-impact part of that system. They keep rural communities viable, anchor seasonal employment, and attract new residents and businesses who want access to the outdoors.

Willamette Pass plays this role in both directions. It draws Willamette Valley residents up into the mountains, and it connects central Oregon communities like La Pine and Crescent with valley-side towns like Oakridge. The mountain becomes a shared meeting ground, a place where a kid from Eugene can share a lift ride with a logger from Oakridge or a nurse from La Pine and, for a few minutes, talk only about snow.

That social glue matters, especially in an era of deep political and cultural division. The mountain doesn’t erase those differences, but it offers a common experience that’s physical, immediate, and real.

Designing for Everyone, Not Just the Few

As Willamette Pass moves into its next phase, one of the most promising threads is its explicit focus on accessibility and inclusion.

The Power Kids pass, with its truly free access for kids 12 and under, is an obvious example. So are super-senior passes and entry-level lesson packages designed to lower the barrier to trying snowsports for the first time.

But inclusion is also cultural. Mindy talks about how the mountain has become more welcoming to Spanish-speaking families, and how her own experience as a young woman on ski patrol—taken seriously from the start—convinced her that a ski hill can be a uniquely healthy place for teens to test themselves and grow.

When staff embrace the reality that people show up with different backgrounds, languages, and economic circumstances, the resort becomes something more than a business. It becomes a community asset: a place where families from diverse cultural and economic backgrounds, from rural or urban spaces, can all access and enjoy.

If the master plan’s summer elements move forward, that inclusive ethos will extend far beyond snow. Lift-served hiking and sightseeing, disc golf courses, and—eventually—mountain bike trails can open the mountain to people who may never strap on sticks or boards. When designed thoughtfully with input from local communities and tribes, those uses can honor the deeper cultural and ecological history of the landscape as well.

Persistence, Creativity, and a Path Forward

Taken together, the story of Willamette Pass is not just about one ski area trying to survive climate change and legal headwinds. It’s about what happens when a community decides that access to the mountains is worth fighting for.

The resort’s very existence rests on a series of stubborn decisions: Roy and Edna Temple cutting a rope tow line in 1941; the Wiper family installing Oregon’s first high-speed six-pack lift despite the objections of financial experts; volunteer patrollers hauling toboggans in storms; and a group of mostly Oakridge-based staff blowing just enough snow to open a magic carpet in 2025 on the leanest Christmas in recent memory.

Now, under MCP’s stewardship and local leadership, Willamette Pass is again choosing the harder route. Instead of selling off or scaling back, the resort is investing in snowmaking, efficient infrastructure, and an ambitious expansion that could double its terrain and solidify its role as a regional pressure-relief valve for overcrowded Northwest winters.

That work is not guaranteed to succeed. It will require careful environmental review, genuine collaboration with tribes and conservationists, thoughtful design for summer uses, and real legislative progress on recreation liability and insurance coverage.

But the opportunity is enormous.

If Willamette Pass can evolve into a four-season, climate-resilient mountain that still feels authentically local—where kids from Oakridge, La Pine, Crescent, and Eugene ski for free, elders keep lapping into their seventies (and beyond), and summer visitors hike, ride, and play on trails that honor both the land and its history—it will stand as a model for what small community ski areas can become.

For businesses considering investment in the region, the message is clear: this is not a dying industry clinging to the last good winters. It’s a community choosing to innovate its way into a new kind of mountain economy—one built on persistence, creativity, and a belief that access to wild, snowy places should belong to everyone, not just the few who can afford a $200 lift ticket. And on a good powder day, standing at the top of Eagle Peak with Odell Lake shining below and Diamond Peak on the horizon, it’s easy to believe that future is worth fighting for.